Back in Brooklyn, trying to address the fact that I essentially have no friends in this town. Acquaintances, yes. Hordes of them. Clients, more and more of them, thankfully. Yoga instructors, yoga classmates, fellow artists, co-op associates, people I shared a table with at Barbés one evening. Friends of people I used to be friends with; people I tried to be friends with and it didn't click. Former almost-team members. Arts administrators and gallerists who sort of know me by sight when I say hello. Friends of my mom's; parents of friends. People I met at parties or in bars or at galleries, who got all enthusiastic, took my phone number, promised to call and never did. People who never called back. Former Nerve dates. Elderly men with crushes on me. Friends of the elderly men, who apparently know me by sight enough so that when the elderly man meets a woman who looks like me, three people in the general vicinity can say, "yes, it looks just like her." Downstairs neighbors. Neighbors who know my car, and ring my doorbell when I forget to move it. Under-recognized musicians I heard at the Living Room, Arlene's Grocery, or Barbés and thought about trying to collaborate with, but didn't pursue it. Other massage therapists who are good enough to refer to, but not quite good enough for me to pay them to work on me.

All of these people would think it was weird if I called them just to say hey. I call people long-distance instead. Most of these people I was fortunate enough to see or speak to over the holiday, and thus they'd think it was weird if I called again now. So I must perforce embrace my loneliness. I wait to emerge out the other side.

Saw the Anselm Kiefer show when I was in Fort Worth; it Blew Me Away. I'm sorry I didn't have time to go again. It's ironic that I grew up in a town that boasted two, and now three, world-class fine art museums, but in other ways is so hidebound, conservative and provincial that I fled at the age of eighteen, and never stayed for more than a week at a time thereafter. Evidently the current curator at the new Fort Worth Museum of Modern Art has been a personal friend of Kiefer's for twenty years, and that's how we scored the show; it's not even coming to New York. More shame New York.

Kiefer is one of the few modern artists I've ever encountered who successfully integrates a cerebral, referential thematic approach with a kinesthetic impact that pulverizes bricks. When approaching one of his works, you can either go read the paragraph of text on the wall beside it which explains the historical, philosophical, theological, and scientific references in the work and how they are used, or you can simply stand in front of it, say 'woooooow' and become pleasantly dizzy. Either way, your perceptual channels are thoroughly engaged. Afterward, I felt like a complete jerk for calling myself an artist. At least I am mature enough to recognize when someone is way, way, way out of my league.

I noticed that Kiefer's studio is in the South of France, which explains why I thought of fields of late-summer sunflowers, all looking down, when I saw some of his paintings. He is described as 'solitary' and hangs out in the NYC gallery scene rarely to never. I started thinking that it may not be a coincidence that the modern artists I truly admire, relate to, study, and would like to emulate--Isamu Noguchi, Lee Bontecou, Andy Goldsworthy, Rufino Tamayo, and Kiefer--are none of them scenesters. The scene does not nurture depth, mastery, humility or spirituality. It nurtures egotism, spectacle and fatuous obscurity. But you already knew that.

Friday, December 30, 2005

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

Chaos theory

My baby cat wakes me up every morning. In fact, he also tucks me in at night. Once I'm horizontal, I will hear a 'thump, scrabble scrabble' which is him climbing the loft; then he stalks up to my head, kneads my chest for a few minutes, and condescends to be petted and baby-talked for a few minutes before curling up on my feet. In the morning, he watches for the first signs of stirring, then repeats the procedure.

Once we are out of the loft and proceeding in state to the cat food dishes, though, I see the inevitable signs that he has NOT been sleeping demurely on my toes all night long. Carpets and painting tarps are rucked up in heaps; wastebaskets are overturned; violently dismembered Q-tips are strewn from one end of the apartment to the other. (I'm embarrassed to reveal this in public, but my cat has an earwax fetish. He is so attuned to the source of this precious elixir that at the very sound of the Q-tip drawer opening, he lurks. He watches the ear-cleaning procedure with apparent nonchalance, and casually glides over to the wastebasket as each one is dropped onto the rubbish with a faint 'plush.' He waits until I've left the bathroom before pouncing; he then hides behind the prone basket in order to surprise the evil Q-tips in their bid for freedom. Over the course of the day he will extract each one, tossing it like a baton until it has been wrestled into submission, and as for the earwax--well, best not to dwell on that.)

So then, every day of my life begins with an act of carpet-straightening, vomit removal, or Q-tip disposal. This is a crucial thing.

One of the primal fears of single women of my generation is that we will turn into old ladies who live with cats. Go ahead, ask any girl between the age of twenty-five and forty--"Aren't you afraid of becoming an old lady who lives with cats?" She will either hit you or burst out sobbing. Thus I write about my cats with trepidation; I keep our relationship very close to my chest. But lately it occurred to me that I need my cats for more than just respite from loneliness, alarm clocks and recipients of idle conversation. My cats provide an injection of vital chaos into my daily routine.

Just think--what would my life be like if, when I got up in the morning, things in my apartment were in exactly the same state of order or disarray as when I went to sleep? What if there were no soil footprints leading from the potted plant across the stove, no grains of cat litter on the rug, and the glue bottle was still wearing its cap? How would I start my day? More specifically--what would be the random, trivial task of adjustment that would serve as a bridge between inertia and conscious action?

Think about it. I'd get up, of course, eventually, cat or no. I'd stumble into the bathroom and stare at the floor. I'd put on the tea kettle, open the New Yorker, shower, dress, and go about my business. But what would there be to start me thinking? What force of nature beyond my control would preserve me from mindless routine? Sure, the phone could ring, there could be a blizzard, a carting company might drop a dumpster on my car. But such miracles cannot daily be counted upon. My cats provide a reliable source of mental jump-starts in my quotidian existence.

I realized, today, that I will never live in a space that looks like something in a magazine. Not because I don't have taste; on the contrary, I have too much taste. Take a look at any perfectly appointed room in any glossy designer magazine; then take a look at the art on the walls. Chances are the art is bad. If not actually bad, chances are it doesn't rise above the mediocre. This is because good art creates a certain amount of visual chaos. I am a woman of very small net worth (although, after doing a spreadsheet this week, I discovered that my net worth is, at least, a positive number), but I DO have an art collection. In addition to the overstock of originals by yours truly, I own a brightly painted, ceramic flying pig with anatomically incorrect udders; an original Julio Mendossa that is cracking disgracefully, partly because of the quality of Mexican paint and partly because the only place to hang it was the bathroom; a puppet from Java; a cat mask from Central America; a large plastic face by Donna Han; a painting of a giant hibiscus by Chris Smith Evans; and too many other strange and wonderful artifacts to enumerate. All of them are weird. None of them match each other or anything else in the apartment.

Someone once explained chaos theory to me like this; say you have a grid full of peaks and valleys, and an ant is climbing patiently over it, searching for the highest peak. If the ant is periodically knocked off whatever hill it happens to be climbing, at random intervals, it is statistically more likely to reach the highest peak in the shortest amount of time, than if it were allowed to keep walking unmolested. That is, random interference and inconsistency of input actually steers us toward enlightenment.

My big cat just punched me in the lip. That means it's time for bed.

Once we are out of the loft and proceeding in state to the cat food dishes, though, I see the inevitable signs that he has NOT been sleeping demurely on my toes all night long. Carpets and painting tarps are rucked up in heaps; wastebaskets are overturned; violently dismembered Q-tips are strewn from one end of the apartment to the other. (I'm embarrassed to reveal this in public, but my cat has an earwax fetish. He is so attuned to the source of this precious elixir that at the very sound of the Q-tip drawer opening, he lurks. He watches the ear-cleaning procedure with apparent nonchalance, and casually glides over to the wastebasket as each one is dropped onto the rubbish with a faint 'plush.' He waits until I've left the bathroom before pouncing; he then hides behind the prone basket in order to surprise the evil Q-tips in their bid for freedom. Over the course of the day he will extract each one, tossing it like a baton until it has been wrestled into submission, and as for the earwax--well, best not to dwell on that.)

So then, every day of my life begins with an act of carpet-straightening, vomit removal, or Q-tip disposal. This is a crucial thing.

One of the primal fears of single women of my generation is that we will turn into old ladies who live with cats. Go ahead, ask any girl between the age of twenty-five and forty--"Aren't you afraid of becoming an old lady who lives with cats?" She will either hit you or burst out sobbing. Thus I write about my cats with trepidation; I keep our relationship very close to my chest. But lately it occurred to me that I need my cats for more than just respite from loneliness, alarm clocks and recipients of idle conversation. My cats provide an injection of vital chaos into my daily routine.

Just think--what would my life be like if, when I got up in the morning, things in my apartment were in exactly the same state of order or disarray as when I went to sleep? What if there were no soil footprints leading from the potted plant across the stove, no grains of cat litter on the rug, and the glue bottle was still wearing its cap? How would I start my day? More specifically--what would be the random, trivial task of adjustment that would serve as a bridge between inertia and conscious action?

Think about it. I'd get up, of course, eventually, cat or no. I'd stumble into the bathroom and stare at the floor. I'd put on the tea kettle, open the New Yorker, shower, dress, and go about my business. But what would there be to start me thinking? What force of nature beyond my control would preserve me from mindless routine? Sure, the phone could ring, there could be a blizzard, a carting company might drop a dumpster on my car. But such miracles cannot daily be counted upon. My cats provide a reliable source of mental jump-starts in my quotidian existence.

I realized, today, that I will never live in a space that looks like something in a magazine. Not because I don't have taste; on the contrary, I have too much taste. Take a look at any perfectly appointed room in any glossy designer magazine; then take a look at the art on the walls. Chances are the art is bad. If not actually bad, chances are it doesn't rise above the mediocre. This is because good art creates a certain amount of visual chaos. I am a woman of very small net worth (although, after doing a spreadsheet this week, I discovered that my net worth is, at least, a positive number), but I DO have an art collection. In addition to the overstock of originals by yours truly, I own a brightly painted, ceramic flying pig with anatomically incorrect udders; an original Julio Mendossa that is cracking disgracefully, partly because of the quality of Mexican paint and partly because the only place to hang it was the bathroom; a puppet from Java; a cat mask from Central America; a large plastic face by Donna Han; a painting of a giant hibiscus by Chris Smith Evans; and too many other strange and wonderful artifacts to enumerate. All of them are weird. None of them match each other or anything else in the apartment.

Someone once explained chaos theory to me like this; say you have a grid full of peaks and valleys, and an ant is climbing patiently over it, searching for the highest peak. If the ant is periodically knocked off whatever hill it happens to be climbing, at random intervals, it is statistically more likely to reach the highest peak in the shortest amount of time, than if it were allowed to keep walking unmolested. That is, random interference and inconsistency of input actually steers us toward enlightenment.

My big cat just punched me in the lip. That means it's time for bed.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

The Kitsch Thing

Warning: This post contains radical dismemberings of the work of two popular artists, Thomas Kinkade and Kenny G. If you are a fan of one of these artists, or if you ARE one of these artists, please stop reading now. It will only hurt your feelings.

This week, I am sorry to say, I turned on my TV. I have no excuse for myself. Somebody mentioned those two fatal words, "Christmas specials," and my seven-year-old id took over. Once it was on--oh, Lord, I don't even want to START the litany of the crap I watched. I feel like I've caught up on ten years' worth of popular culture. "Sex and the City," "CSI," "Frazier," and "Las Vegas" were vaguely familiar but meaningless terms to me until now. With fortitude and discipline, soon they will be again.

Watching so little TV, I am likewise Not Inured to Commercials. In my seven to ten-year intervals between bouts of TV-watching, things change a lot; crass materialism becomes ever crasser and more materialistic. The last time I did a dose of TV, sometime around 1998, a car commercial came on with the tagline, "I may not have all the answers, but at least I have a new car!" I went into a state of shock that lasted for weeks.

This time was no different. Car commercials, diamond commercials, "the best gift award--Old Navy Sweaters!" rolled by in an unending stream of fey hype and shouting. By contrast, the spots for "Glade Holiday Candles With Scenes by Thomas Kinkade" and "Kenny G Holiday Hits" should have seemed restrained and wholesome. But nevertheless I have decided to devote this week's post to explaining, in excrutiating detail, why it was these particular ads that made me want to vomit.

I might as well admit upfront that I could be seen to have a professional grudge against Thomas Kinkade, because, well, he's probably a squillionaire by now, and with a bit of luck I may be able to scrape together next month's rent. But my issue with him is not directly financial; in fact, I support the aggressive teaching of sales, marketing and bookkeeping skills in art institutions. My issue with Thomas Kinkade is that his work is vile, fatuous kitsch. Harmless, perhaps. But perhaps not.

Kitsch, as I have explained elsewhere, can be defined as "the pretense that shit does not exist." It's a prettification, a smoothing-down of gritty and troubled perceptions. Surely this can't be wrong; surely such quiet sweetness can provide a sense of peace and respite, however temporary, from a world of drudgery and strife. Nevertheless, it is a lie; and contrary to providing true peace, kitschy perceptions blunt and obscure it.

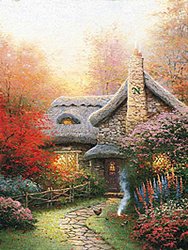

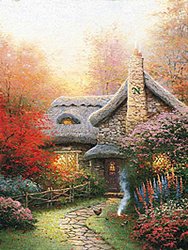

Let me illustrate. Here is a picture by Thomas Kinkade.

For those of you eight or ten readers who have successfully avoided encountering this artist's work, I may say that this piece is fairly typical. Note the semi-rural setting, the cozy dwelling with warm glow emanating from windows, the profusion of flowers, the filtered light, the brilliant foliage. Note, furthermore, from a compositional standpoint: the frontal, standing-on-the-ground horizontal perspective, the gently winding path, the diagonal line of the fence. Grass and flowers in foreground, house in the middle, trees as backdrop. I had a book as a kid called "It's Fun To Make Pictures;" the instructions for "How To Paint A Landscape" taught you how to compose a painting that looked like this--verbatim.

For those of you eight or ten readers who have successfully avoided encountering this artist's work, I may say that this piece is fairly typical. Note the semi-rural setting, the cozy dwelling with warm glow emanating from windows, the profusion of flowers, the filtered light, the brilliant foliage. Note, furthermore, from a compositional standpoint: the frontal, standing-on-the-ground horizontal perspective, the gently winding path, the diagonal line of the fence. Grass and flowers in foreground, house in the middle, trees as backdrop. I had a book as a kid called "It's Fun To Make Pictures;" the instructions for "How To Paint A Landscape" taught you how to compose a painting that looked like this--verbatim.

From a technical standpoint, then, I'd have to say his work is competent. Not inventive, but sound. Now, let's examine his palette. "Colorful," you say. "More or less realistic, but bright; idealized," you might observe, if you were to articulate your impressions. Indeed, this is why every middle-class family in the Midwest has one on the wall; it's pretty. If we were to get analytical, we would see that he has used colors from all round the color wheel; the vivid orange of the leaves counterbalanced by the soft blue-gray of the roof, the pastel pinks and blues of the flowerbeds popping against the whispery greens of the lawn, anchored by luminous yellows of window-light and deep charcoal shadows. Everything is balanced--and utterly predictable.

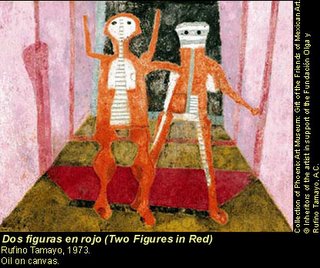

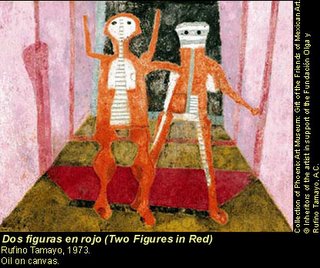

By way of contrast, here is a picture by Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo.

I have to say that I'm somewhat biased, having spent an inordinate percentage of my trip to Mexico City in the Rufino Tamayo Museum, gawping and having my entire conception of art and reality drastically altered. But even in the shadowy inadequacies of miniscule size and 72 dpi Internet re-re-production, one can see that this is an exceptionally stupid painting. Come on, those figures look like they were drawn by a four-year-old. And the colors! Pepto-bismol pink, clashing with blood red, burnt orange, puke ochre and flat black. Bleah. You speak of kitsch, you say--look at those asinine figures! Arms upraised in gesture of inane celebration on the left, straight-lined, skeletal smile on the right! Why This Stuff Gets Into Museums. I Mean.

You will have to take it on faith, then, that the experience of standing in front of a painting by Rufino Tamayo in his museum in Mexico City is akin to spending 20 minutes in a 210 degree Russian sauna, then having a buffed-out masseuse throw a bucket of cold water over your head and thrash you for half an hour with an oakleaf featherduster. For Those Who Have Eyes To See, as they say.

Here's an exercise, which I might entitle, on the spur of the moment, the Robert Irwin Perceptual Meditation. As you go through your day, try to note what your eyes are seeing. Not what your brain interprets as what your eyes are seeing; try to discover the mere shapes, angles, colors and impressions that your eyes are actually registering. Try to reduce these perceptions to a system of shapes and colors, as though the world were a complex game of Tetris; vertical, horizontal, angular, big, small, color gray, color beige, color blue-gray or lavender. Practice this for a few hours, or one whole day. Then when you are done, tally up the number and percentage of moments when you were actually perceiving the world as a system composed of foreground, middle ground, and backdrop, from a frontal perspective, with a balanced rendering of vivid colors from all round the color wheel. Unless you are a real-estate photographer, my guess would be--almost never.

My point is that a Thomas Kinkade painting is not a picture of a house. It's not even a picture of an ideal, snug, peaceful, cozy house in your happiest dreams. It is a picture of what the lowest common denominator of centuries of cultural symbolism has told you is a picture of a house. It's actually a very potent block between your experience, your perceptions, and your imagination. By providing ubiquitous, unimaginative, bland symbols of a grit-free 'peace' that never existed, kitschy paintings are teaching you to disconnect from the unique experience of your own life.

Perhaps that's hyperbolic. But back to Tamayo.

Standing in front of a Tamayo, let's say in the toxic atmosphere of a dangerously polluted city at an altitude that's giving you a migraine, the first thing you might notice is that those are some weird-ass colors. Moreover, they clash; moreover, they're dirty. Really, it looks like he's poured sand into his paint. If it's pink, it's only pink on the surface, although on the surface it's a strangely loud pink; underneath and peeking through, mixed in with the sand, is a lot of dull gray, and flecks of blue and tan and improbable red. He puts screamingly bright colors either next to each other, screaming in entirely different languages, or next to the dullest, ugliest colors you ever saw--reference, in the painting above, that nasty olive-brown floor, host to some orange feet and a red trapezoid.

Then when you look at his composition, you notice that he's breaking so many rules that he's created a new system of rules entirely. There is not a single instance of symmetry, plumb verticality or horizontality in the entire painting, except for the vertical-horizontal lines within the figures' heads, right where they're not supposed to be. Nothing is consistent, everything is new; for instance, the calves of the figure on the left are vaguely anatomically delineated, the rest is a riff halfway between stick-figure and crypto-Cubist nightmare.

Every bit of this painting, in fact, is a surprise. And it's that way with every painting in the museum. You go through, wondering if you could stand to have any of them in your home, but each one of them has at least one element that makes you profoundly uncomfortable.

At the same time, this Tamayo guy seems like he must have been a relatively cheerful fellow. So many of the figures are smiling; he paints a lot of couples, families, landscapes and watermelons. Ordinary things. Life things. But he paints them like nobody else on the planet.

Perhaps, though, if every person on the planet got in touch with his or her own true perceptions and started to paint, without reference to pervasive cultural symbology, this might be a planet of four billion unique artists. And such discussions we'd have then!

Utopian ideals aside--the final point I'd like to make about Tamayo, and about painting in general, is that once you get used to it, it's the relationships between colors and forms that make them beautiful, rather than the colors and forms themselves. Radical contrast breeds excitement, complex harmony, and a beauty that is rich, deep and all-inclusive. Kitsch is about avoidance--it edits out any awkwardness, any reference to death and decay, to comfort the mind's fears. But great art puts in the death; great art accepts everything. And unconditional acceptance is a prerequisite for enduring peace.

Once I owned an album by Kenny G. It came from one of those record clubs, where you get twenty albums for a penny. I put it on and was physically unable to listen to the entire thing. I'm not even sure I made it to the second side. 'Elevator music' was what we used to call it, back in Texas; also 'dentist office music'. (My childhood dentist wore the men's cologne, "Pour Lui;" for decades I thought that this was the smell of his distinctly ineffective anaesthetic. I didn't realize that it was supposed to be a good smell until I opened an issue of GQ one day and my gums began to hurt.) So maybe my dislike of Kenny G is a purely situational association, having nothing to do with the quality of the music itself.

But the thirty-second commercial for "Kenny G's Holiday Hits" still made me shudder as though some stranger had dripped snot down my collar. So, in a spirit of analysis and investigation, I downloaded a couple of Holiday Hits, to try to figure out what it was that bothered me so much.

Indeed, like Kinkade, the man has command of his instrument. He hits all the notes, sweetly if predictably. What started the hives on my neck might be called his "touch." He strokes each note like a pedophile patting an eight-year-old--with such conscious mildness that it borders on the creepy. There's a pathological avoidance of any untoward passion, harshness or 'edge.' The instrumental backup reinforces this saccharinity; disenfranchised drums keep a beat that never skips, wavers or syncopates, punctuated by emasculated harps and swells of synthesized strings, forcing a hypocritical climax. 'Twee,' that's the word for it, 'twee.'

My God, I sound like a wine critic.

Just to decompress, I then launched one of the greatest jazz holiday hits of all time, John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things." Ahhhhhh. Relief. Saint John and his band thwack into glorious dissonance with that first inimitable chord, crashing on the bass like an oncoming army; THONK da-duh-dah, THRONK da-duh-daa-duh...and then when the sax comes in for the melody, it's fifty percent grime, nasal and joyous; BONK-bap-bap BONK bop-bop DONK bop-bop BOP-bop...breaking it down, I noticed that that army bass in the piano never lets up. The underlying rhythm is dissonance itself. Above it, John on soprano saxophone deedles insouciantly like a drunk on a tightrope, wandering whither he might. This approximates joy; playing music without a net from your scarred heart, while the clock is ticking and the unpaid landlord pounds on the door.

Now I sound like a pulp novelist. This is why I never read music criticism.

Purple prose aside, the point remains the same--Art is not Art if it skirts the dissonance; it's commercialised pablum for the masses. And who are the masses? Not you, not me, not anybody. Societies without mass media do not have kitsch. It's aesthetic junk food. It bloats the body and blunts the soul, channelling individual creativity onto an interstate leading nowhere.

Well, so what? It's just art. Art is a luxury anyway; it has little to do with a happy life.

No, at the risk of getting didactic--art mirrors life, which mirrors art. If, as a culture, our art becomes impoverished, avoidant, saccharine and twee, we absorb a false and dangerously destructive message about the nature of happiness. A close friend of mine told me that her boyfriend recently said, "I keep expecting our relationship to settle down and be peaceful." She told him, "You've known me for six years and it's never been that way. Do you really think I'll change?" Peaceful does not, and will never, equal sweet, uneventful and bland.

Too many people think that strife and conflict have no place in a peaceful world--that if problems arise in a relationship, for example, then you are with the wrong person and must drop it and start over. Or, conversely, that if you grew up in a seriously dysfunctional, abusive family, and are so emotionally damaged that you'll never live in a Thomas Kinkade house even in fantasy, that the best you can hope for is to sweep your dreams under the rug, deny the pain, avoid intimacy, and live a half-life on the fringes of light and laughter.

The reason that kitsch is a tragic lie is that it represents the opposite of peace. It constructs a cruel, inarguable, ironclad judgment by what it omits--and it omits almost everything. Healing is grounded in acceptance of everything. Once placed in perspective, once looked at fully and loved, the sand in the paint is what makes it beautiful.

This week, I am sorry to say, I turned on my TV. I have no excuse for myself. Somebody mentioned those two fatal words, "Christmas specials," and my seven-year-old id took over. Once it was on--oh, Lord, I don't even want to START the litany of the crap I watched. I feel like I've caught up on ten years' worth of popular culture. "Sex and the City," "CSI," "Frazier," and "Las Vegas" were vaguely familiar but meaningless terms to me until now. With fortitude and discipline, soon they will be again.

Watching so little TV, I am likewise Not Inured to Commercials. In my seven to ten-year intervals between bouts of TV-watching, things change a lot; crass materialism becomes ever crasser and more materialistic. The last time I did a dose of TV, sometime around 1998, a car commercial came on with the tagline, "I may not have all the answers, but at least I have a new car!" I went into a state of shock that lasted for weeks.

This time was no different. Car commercials, diamond commercials, "the best gift award--Old Navy Sweaters!" rolled by in an unending stream of fey hype and shouting. By contrast, the spots for "Glade Holiday Candles With Scenes by Thomas Kinkade" and "Kenny G Holiday Hits" should have seemed restrained and wholesome. But nevertheless I have decided to devote this week's post to explaining, in excrutiating detail, why it was these particular ads that made me want to vomit.

I might as well admit upfront that I could be seen to have a professional grudge against Thomas Kinkade, because, well, he's probably a squillionaire by now, and with a bit of luck I may be able to scrape together next month's rent. But my issue with him is not directly financial; in fact, I support the aggressive teaching of sales, marketing and bookkeeping skills in art institutions. My issue with Thomas Kinkade is that his work is vile, fatuous kitsch. Harmless, perhaps. But perhaps not.

Kitsch, as I have explained elsewhere, can be defined as "the pretense that shit does not exist." It's a prettification, a smoothing-down of gritty and troubled perceptions. Surely this can't be wrong; surely such quiet sweetness can provide a sense of peace and respite, however temporary, from a world of drudgery and strife. Nevertheless, it is a lie; and contrary to providing true peace, kitschy perceptions blunt and obscure it.

Let me illustrate. Here is a picture by Thomas Kinkade.

For those of you eight or ten readers who have successfully avoided encountering this artist's work, I may say that this piece is fairly typical. Note the semi-rural setting, the cozy dwelling with warm glow emanating from windows, the profusion of flowers, the filtered light, the brilliant foliage. Note, furthermore, from a compositional standpoint: the frontal, standing-on-the-ground horizontal perspective, the gently winding path, the diagonal line of the fence. Grass and flowers in foreground, house in the middle, trees as backdrop. I had a book as a kid called "It's Fun To Make Pictures;" the instructions for "How To Paint A Landscape" taught you how to compose a painting that looked like this--verbatim.

For those of you eight or ten readers who have successfully avoided encountering this artist's work, I may say that this piece is fairly typical. Note the semi-rural setting, the cozy dwelling with warm glow emanating from windows, the profusion of flowers, the filtered light, the brilliant foliage. Note, furthermore, from a compositional standpoint: the frontal, standing-on-the-ground horizontal perspective, the gently winding path, the diagonal line of the fence. Grass and flowers in foreground, house in the middle, trees as backdrop. I had a book as a kid called "It's Fun To Make Pictures;" the instructions for "How To Paint A Landscape" taught you how to compose a painting that looked like this--verbatim.From a technical standpoint, then, I'd have to say his work is competent. Not inventive, but sound. Now, let's examine his palette. "Colorful," you say. "More or less realistic, but bright; idealized," you might observe, if you were to articulate your impressions. Indeed, this is why every middle-class family in the Midwest has one on the wall; it's pretty. If we were to get analytical, we would see that he has used colors from all round the color wheel; the vivid orange of the leaves counterbalanced by the soft blue-gray of the roof, the pastel pinks and blues of the flowerbeds popping against the whispery greens of the lawn, anchored by luminous yellows of window-light and deep charcoal shadows. Everything is balanced--and utterly predictable.

By way of contrast, here is a picture by Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo.

I have to say that I'm somewhat biased, having spent an inordinate percentage of my trip to Mexico City in the Rufino Tamayo Museum, gawping and having my entire conception of art and reality drastically altered. But even in the shadowy inadequacies of miniscule size and 72 dpi Internet re-re-production, one can see that this is an exceptionally stupid painting. Come on, those figures look like they were drawn by a four-year-old. And the colors! Pepto-bismol pink, clashing with blood red, burnt orange, puke ochre and flat black. Bleah. You speak of kitsch, you say--look at those asinine figures! Arms upraised in gesture of inane celebration on the left, straight-lined, skeletal smile on the right! Why This Stuff Gets Into Museums. I Mean.

You will have to take it on faith, then, that the experience of standing in front of a painting by Rufino Tamayo in his museum in Mexico City is akin to spending 20 minutes in a 210 degree Russian sauna, then having a buffed-out masseuse throw a bucket of cold water over your head and thrash you for half an hour with an oakleaf featherduster. For Those Who Have Eyes To See, as they say.

Here's an exercise, which I might entitle, on the spur of the moment, the Robert Irwin Perceptual Meditation. As you go through your day, try to note what your eyes are seeing. Not what your brain interprets as what your eyes are seeing; try to discover the mere shapes, angles, colors and impressions that your eyes are actually registering. Try to reduce these perceptions to a system of shapes and colors, as though the world were a complex game of Tetris; vertical, horizontal, angular, big, small, color gray, color beige, color blue-gray or lavender. Practice this for a few hours, or one whole day. Then when you are done, tally up the number and percentage of moments when you were actually perceiving the world as a system composed of foreground, middle ground, and backdrop, from a frontal perspective, with a balanced rendering of vivid colors from all round the color wheel. Unless you are a real-estate photographer, my guess would be--almost never.

My point is that a Thomas Kinkade painting is not a picture of a house. It's not even a picture of an ideal, snug, peaceful, cozy house in your happiest dreams. It is a picture of what the lowest common denominator of centuries of cultural symbolism has told you is a picture of a house. It's actually a very potent block between your experience, your perceptions, and your imagination. By providing ubiquitous, unimaginative, bland symbols of a grit-free 'peace' that never existed, kitschy paintings are teaching you to disconnect from the unique experience of your own life.

Perhaps that's hyperbolic. But back to Tamayo.

Standing in front of a Tamayo, let's say in the toxic atmosphere of a dangerously polluted city at an altitude that's giving you a migraine, the first thing you might notice is that those are some weird-ass colors. Moreover, they clash; moreover, they're dirty. Really, it looks like he's poured sand into his paint. If it's pink, it's only pink on the surface, although on the surface it's a strangely loud pink; underneath and peeking through, mixed in with the sand, is a lot of dull gray, and flecks of blue and tan and improbable red. He puts screamingly bright colors either next to each other, screaming in entirely different languages, or next to the dullest, ugliest colors you ever saw--reference, in the painting above, that nasty olive-brown floor, host to some orange feet and a red trapezoid.

Then when you look at his composition, you notice that he's breaking so many rules that he's created a new system of rules entirely. There is not a single instance of symmetry, plumb verticality or horizontality in the entire painting, except for the vertical-horizontal lines within the figures' heads, right where they're not supposed to be. Nothing is consistent, everything is new; for instance, the calves of the figure on the left are vaguely anatomically delineated, the rest is a riff halfway between stick-figure and crypto-Cubist nightmare.

Every bit of this painting, in fact, is a surprise. And it's that way with every painting in the museum. You go through, wondering if you could stand to have any of them in your home, but each one of them has at least one element that makes you profoundly uncomfortable.

At the same time, this Tamayo guy seems like he must have been a relatively cheerful fellow. So many of the figures are smiling; he paints a lot of couples, families, landscapes and watermelons. Ordinary things. Life things. But he paints them like nobody else on the planet.

Perhaps, though, if every person on the planet got in touch with his or her own true perceptions and started to paint, without reference to pervasive cultural symbology, this might be a planet of four billion unique artists. And such discussions we'd have then!

Utopian ideals aside--the final point I'd like to make about Tamayo, and about painting in general, is that once you get used to it, it's the relationships between colors and forms that make them beautiful, rather than the colors and forms themselves. Radical contrast breeds excitement, complex harmony, and a beauty that is rich, deep and all-inclusive. Kitsch is about avoidance--it edits out any awkwardness, any reference to death and decay, to comfort the mind's fears. But great art puts in the death; great art accepts everything. And unconditional acceptance is a prerequisite for enduring peace.

Once I owned an album by Kenny G. It came from one of those record clubs, where you get twenty albums for a penny. I put it on and was physically unable to listen to the entire thing. I'm not even sure I made it to the second side. 'Elevator music' was what we used to call it, back in Texas; also 'dentist office music'. (My childhood dentist wore the men's cologne, "Pour Lui;" for decades I thought that this was the smell of his distinctly ineffective anaesthetic. I didn't realize that it was supposed to be a good smell until I opened an issue of GQ one day and my gums began to hurt.) So maybe my dislike of Kenny G is a purely situational association, having nothing to do with the quality of the music itself.

But the thirty-second commercial for "Kenny G's Holiday Hits" still made me shudder as though some stranger had dripped snot down my collar. So, in a spirit of analysis and investigation, I downloaded a couple of Holiday Hits, to try to figure out what it was that bothered me so much.

Indeed, like Kinkade, the man has command of his instrument. He hits all the notes, sweetly if predictably. What started the hives on my neck might be called his "touch." He strokes each note like a pedophile patting an eight-year-old--with such conscious mildness that it borders on the creepy. There's a pathological avoidance of any untoward passion, harshness or 'edge.' The instrumental backup reinforces this saccharinity; disenfranchised drums keep a beat that never skips, wavers or syncopates, punctuated by emasculated harps and swells of synthesized strings, forcing a hypocritical climax. 'Twee,' that's the word for it, 'twee.'

My God, I sound like a wine critic.

Just to decompress, I then launched one of the greatest jazz holiday hits of all time, John Coltrane's "My Favorite Things." Ahhhhhh. Relief. Saint John and his band thwack into glorious dissonance with that first inimitable chord, crashing on the bass like an oncoming army; THONK da-duh-dah, THRONK da-duh-daa-duh...and then when the sax comes in for the melody, it's fifty percent grime, nasal and joyous; BONK-bap-bap BONK bop-bop DONK bop-bop BOP-bop...breaking it down, I noticed that that army bass in the piano never lets up. The underlying rhythm is dissonance itself. Above it, John on soprano saxophone deedles insouciantly like a drunk on a tightrope, wandering whither he might. This approximates joy; playing music without a net from your scarred heart, while the clock is ticking and the unpaid landlord pounds on the door.

Now I sound like a pulp novelist. This is why I never read music criticism.

Purple prose aside, the point remains the same--Art is not Art if it skirts the dissonance; it's commercialised pablum for the masses. And who are the masses? Not you, not me, not anybody. Societies without mass media do not have kitsch. It's aesthetic junk food. It bloats the body and blunts the soul, channelling individual creativity onto an interstate leading nowhere.

Well, so what? It's just art. Art is a luxury anyway; it has little to do with a happy life.

No, at the risk of getting didactic--art mirrors life, which mirrors art. If, as a culture, our art becomes impoverished, avoidant, saccharine and twee, we absorb a false and dangerously destructive message about the nature of happiness. A close friend of mine told me that her boyfriend recently said, "I keep expecting our relationship to settle down and be peaceful." She told him, "You've known me for six years and it's never been that way. Do you really think I'll change?" Peaceful does not, and will never, equal sweet, uneventful and bland.

Too many people think that strife and conflict have no place in a peaceful world--that if problems arise in a relationship, for example, then you are with the wrong person and must drop it and start over. Or, conversely, that if you grew up in a seriously dysfunctional, abusive family, and are so emotionally damaged that you'll never live in a Thomas Kinkade house even in fantasy, that the best you can hope for is to sweep your dreams under the rug, deny the pain, avoid intimacy, and live a half-life on the fringes of light and laughter.

The reason that kitsch is a tragic lie is that it represents the opposite of peace. It constructs a cruel, inarguable, ironclad judgment by what it omits--and it omits almost everything. Healing is grounded in acceptance of everything. Once placed in perspective, once looked at fully and loved, the sand in the paint is what makes it beautiful.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Apologies for former post

On second thought, after looking at it again, that S.C. Justice site HAS to be a joke. Nobody who is gainfully employed in a position of responsibility would have time to read my blog, let alone my website, looking for ways to abuse me. I formally apologize for denigrating some bored office worker's innocent sense of humor.

Monday, December 05, 2005

Banality rules

Wouldn't you think that a satirical blog, purporting to be that of a Supreme Court Justice nominee, would be imaginative and pointed and creative and funny? And wouldn't you think that the blog of a real Supreme Court Justice nominee might be, well, deep and insightful and informed and lively? Instead of banal, venal, fatuous and smug? Oh, I forgot, he's a Bush Administration nominee. Never mind.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)